Professor Mair | Projects

Current Projects

West African English on the Move

New Forms of English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) in Germany

Welcome to the homepage of WAfrE on the Move, a research project that has been funded since 1 October 2019 by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, grant #MA 1652/12-1). The point of our research is that postcolonial Englishes from West Africa – for example Nigerian English, Cameroonian English, Gambian English and Ghanaian English – will not be studied in their home territories, nor even in displaced but majority Anglophone diasporic settings such as the UK, the US or Canada, but in Germany, where West African immigrants use English as a lingua franca alongside German, the dominant language in the country. The focus of our research is on language and linguistics, the primary goals being:

- to compile a rich and up-to-date database for the study of new uses of English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) in a German-speaking context;

- to use the data to study the linguistic properties of immigrants’ English:

- to document the extent and communicative/social function of English-German language mixing;

- to obtain ethnographic information on speakers’ communication strategies, language attitudes and ideologies;

- to redress a bias in the study of ELF in Germany, which has so far mainly focused on elite social domains such as English Medium Instruction (EMI) in higher education and ELF in business communication.

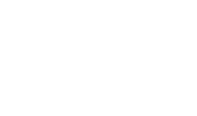

At the core of our database are interviews with individuals and focus groups in which we discuss research participants’ language biographies, focusing both on the time spent in their African countries of origin and, subsequently, in transit and in Germany. We are aware that the value of the interviews is not restricted to linguistics. As our interviewees frequently share information about aspects of their experience other than language and communication, our data qualify as first-rate oral history material about a recent and very dynamic episode in the history of immigration to Germany. A first statistical orientation about current trends is provided by census data, in particular the Ausländerzentralregister (central register of foreign residents). It gives the following figures for the years 2011 and 2018 for the four West African countries accounting for most of the immigration from this region:

Figure 1: Foreign nationals from four West African countries in Germany – 2011 to 2019

Note that these figures considerably under-report the size of the relevant communities. For example, they do not cover illegal immigrants and all those first- and second-generation immigrants who have German citizenship. What is obvious, though, are the steep increases for all four countries during the period of observation.

In due course, we intend to make portions of our data available to researchers from other disciplines with an interest in migration, such as history, sociology, and ethnography. In addition, we are keen to enter into dialogue with members of the general public who are interested in issues of language and integration, with teachers of Deutsch als Fremdsprache, with institutions or volunteers working with migrants, and – most importantly, of course – with members of the African community in Germany. If interested, please get in touch with us via the contact form.

Team

|

Samson Ajagbe holds a PhD in Sociology from the University of Freiburg, Germany. He has combined his current research associate position in this project on West African Englishes with teaching a course on “Social and Educational Works with Refugees” at the Katholische Hochschule Freiburg. These commitments, which have sparked his interest in migration and language study, inspired his current research on the sociology of language and the globalization of African languages. |

|

Uyi Edegbe (post-doc researcher) has a PhD in Sociology from the institute of Sociology, University of Freiburg. His research focuses on transnational migration, remittances and sustainable development. The current project builds on his past research on migration, transnational migrants and their contributions to social development of their home countries. |

|

Bridget Fonkeu (post-doc researcher) who is a member of the team of investigators is a native speaker of West African Pidgin. She has been a teaching and research assistant of English linguistics at the university of Bochum for four years and at the university of Dortmund for three years. This research is in line with her previous investigations on West African Englishes in the German diaspora. |

|

Christian Mair (principal investigator) has been a professor of English linguistics at the University of Freiburg since 1990, his research focuses being corpus linguistics and World Englishes. The current project builds on his previous research on West African Englishes, pidgins and creoles as used on the internet. He’s glad to face the challenges of working with real speakers for a change. |

|

Julia Müller (doctoral researcher) |

|

Rafaela Tosin (research assistant) is a M.A. student of English linguistics at the University of Freiburg. They have a degree is social sciences and in English. Their interests include sociolinguistics, sociophonetics, linguistic antropology and computational linguistics. |

|

Isolde Bonnet (doctoral researcher) |

Associates and consultants:

| Axel Bohmann is assistant professor for English linguistics at the University of Freiburg. His research interests include language and globalization, sociolinguistics, and corpus linguistics, which he approaches through a combination of statistical and discourse-analytical methods. His current Habilitation research focuses on language among asylum seekers in Southwestern Germany and is thus closely related to the present project. | |

| Miriam Neuhausen (research assistant), a Ph.D. student in English linguistics, normally works on a secluded Pennsylvania German-speaking community in Ontario, Canada. She is primarily interested in how language is used in lesser-studied communities that are not mainstream and not monolingual and how speakers in these communities use language to express different identities. |

Our local partners in Freiburg:

Sample Data

Why is German a difficult language to learn? |

|

| Excerpt 1 | |

| "due to me like uh the way the country te- the country challenge is not an excuse (.) but you look like the circumstances around you is uh big big big big challenge because you are not settled (.) so for you to learn it for you to learn German is difficult if you settle it's it's relieved a bit but is not an excuse but the same time is an excuse" | |

| Excerpt 2 | |

|

"the language (.) that's a very very very big barrier because you've already you you have never come across it before it took me time before I could rememeber there were some kind of super prize we used to watch on eighty eight in Nigeria also there were some German eh super prize but we used to make fun of it and it was a very nice movie but (.) we never knew we we would end up here and be faced with speaking the language we know everybody has their mother tongue but we just believe commonly that everyb- everywhere you go English is being spoken" |

|

| Excerpt 3 | |

| "most people find it difficult to believe that I actually learned my German language from eh let me say this eh Kindersendung cartoons that is where I learned my language I didn't have any German friends I couldn't talk to anybody because they wouldn't respond to you so I was much more in doors but personally speaking or truthfully speaking about two years is [YEAR] til almost middle [YEAR] that was almost two years I fought the language I I refused personally not to want to learn the language even when opportunities were presented to me to go to some [INSTITUTION] courses in [PLACE] later I took them but in the very beginning I refused I was like this is a strange language I already know my English I already know my mother tongue I already have another Nigerian language in my head and I am looking for Kinder persons and I have to but starting another language again" | |

English, Pidgin, and German: language mixing |

|

| Excerpt 1 | |

| "they were pushing me say you have to get a job if you don't get a job it's the criteria for your paper because the Bundesamt will check that in my Asyl case so now another lawyer push further to the heart Anfall condition in [CITY] and so I was being asked zuerst I need to provide with like uh fifty signed petitions from so to say eh (- - -) but more so to say the (files) that put poeple in the system that can attest to say they know me funny enough I had that challenge but I knew some people based on this Verein I was telling you the Asylheim they (can now contact) this I built there so I called most of them on phone send them e-mails ah this is my case and I'm being threatened with deportation and my lawyer asked if I could get a signed petition from some people that are they know my character they can vouch for me something of that nature man I was supposed to bring at least fifty or so my brother I got at the end of the day almost close to three hundred was what I got because those that know me they were telling their families telling their uncles anties Omas niece nephews they were writing" | |

| Excerpt 2 | |

| "inside the English I just make ach so inside and ach so is a German word which is in English I still don't know I forgot what it means but I just making just to combine the the sentence together or if I remember something and then I say ah ach so yeah which is in En- in Nigeria or somewhere else they will ask you what is that what are you saying" | |

| Excerpt 3 | |

| "we don't speak it [Pidgin] with the children we speak it when we meet our African brothers and sisters outside when we go out you know even in Nigeria we have eh like eh like three over three hundred eh eh Muttersprache yeah so now eh imagine other African countries they will have their own eh mother tongue too so anytime we meet ourselves outside we just start how you dey now what's up ah you know we speak eh Pidgin English with them" | |

“Asyl makes your head kaputt” |

|

| Excerpt 1 | |

| "uh like like people always say some poeple says uh when you are from when you're not a German Ausländer they say you take their work ah @ which is not possible you can't even take a German his work away it's not possible because they are working you @ can't work how a German is working it's not possible it's not our culture to work that much how they are working so their understanding is so I don't know ah some people say yeah when you are in Asyl you get a lot of money you're sleeping when the people in Asyl want to work but they are not allowed to work (obwohl) yeah but the people in the city thinks the people in Asyl are sleeping and getting money which is half of them want to work but you know it's just this they have this understanding and it's really really not nice" | |

| Excerpt 2 | |

| "we never had that luxury my brother [compared to today] we were collecting eh them two thousand and eight to I think almost or thirteen or so all the changes law we are collecting eh Gutschein of sixty five euro every month Gutschein and this Gutschein we can only use it in [SUPERMARKET] and [SUPERMARKET] and it's not even every day you're only allowed to use it in [SUPERMARKET] Monday where is this and plus this so anything außer these three these I mentioned like Saturdays and Fridays they are not supposed to come to [SUPERMARKET] (it is) if you come to a (- - - - - -) (.) and again when you buy for instance you buy body spray or perfume depending on who is the casheer is they will take out the body spray and perfume and say there's alcohol in it say with the Gutschein you are du darfst kein Alkohol kaufen my brother do you understand me now we are talking of body spray am I going to drink it so I I'm not buying beer it's embarassing you know German will stand behind you in the cue they'll be stretching their neck what is this guy paying with that is not even money you know it was really really embarassing and if you buy like plastic plastic Becher or something they will remove it and say no say the Gutschein cannot buy this you cannot pay for Gutschein with this you know they pick what you pi- what you choose and they will take out some things and tell you say these are the things that your Gutschein can buy it's embarassing so and people (- -) because it's a kind of delay on the cue you know and people will be stretching what is this Ausländer doing there you know very embarassing thing" | |

| Excerpt 3 | |

| "actually I just use my own just for them to be strong I don’t need to use anybody experience my own experience's is enough for me to encourage them you understand five years in Asyl is not einfach at all it's not it wasn’t easy at all we bekomme forty euro in the month now it’s even different they are enjoying you know then we are only we bekomme just forty euro then Schein Gutschein of seventy-nine Euro in two weeks how are we going to eat seventy (to) eighty eighty euro food in two weeks" | |

Language attitudes and ideologies |

|

| Excerpt 1 | |

| [answering to why he speaks Pidgin to his daughter] "uhm because I want her to understand at least a complete different language which is I can which we can also share (our) with African so Pidgin English is I would say something from Africa so I try to make her this way because she say Yoruba is too difficult so Pidgin English she understand English already so it's easy for her to understand Pidgin English" | |

| Excerpt 2 | |

| "in America when you see a lot of people with African name and they can't speak Pidgin English it's like oh they don't even also share their (-) with African then it's completely wrong so when you have the name when you have everything from African at least you should try to to blend in somewhere so this is why I'm just trying to have a bit with with this type of language" | |

| Excerpt 3 | |

| "when I'm speaking Yoruba I can't do that [mix with German] because Yoruba is a complete another language which is not close to English so it's not possible that you mix it yeah the (highest that) I can mix with Yoruba is I think Pidgin English sometimes" | |

| Excerpt 4 | |

| "we speak Pidgin that is our most comfortable language and why are (we) speak Pidgin is I have I have had this I've i've I've I've had this situation nearby I spoke English with my Nigerian brothers and later I was hearing something behind like is this guy feeling like he's too educated for them based on how I was speaking I was being myself" | |

| Excerpt 5 | |

| [answering if she/they speak Pidgin to their children] "ah dat one naa dat one naa street language" | |

Presentations and Publications

Ajagbe, Samsondeen (2022). “Knowledge Production and the Linguistic Market Place: the Case of Nigeria.” In Marie-Joseé Lavallée, ed. In The End of Western Hegemonies?. Wilmington, Delaware: Vernon Press.

Mair, Christian (2020). "English in the German-speaking world: an inevitable presence." In Raymond Hickey, ed. English in the German-speaking world. Cambridge: CUP, 2020. 13-30.

Mair, Christian (2018). "Stabilising domains of English-language use in Germany: Global English in a non-colonial languagescape." In Sandra Deshors, ed. Modeling World Englishes: Assessing the interplay of emancipation and globalization of ESL varieties. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2018. 45-75.

Project Archive

ICE-Jamaica

Compilation of the Jamaican Component of The International Corpus of English

Most Jamaicans tend to think of themselves as English-speaking and therefore regard Patois, the creole language spoken in Jamaica, as some kind of English. Meanwhile, to many linguists it would seem quite plausible to consider English and Patois (the folk designation for Jamaican Creole) two distinct languages in view of the far-reaching differences in syntax and sound pattern. The chief problem for a linguistic description of Caribbean English usage today is to model the relationship between English and the various English-lexifier creoles of the region.

In compiling the "Caribbean" component of ICE it has been decided to sample only texts from Jamaica, the most populous and a culturally very influential community. The make-up of the current release of ICE-Jamaica is heavily biassed towards the written component. Not only has sampling been more difficult for the spoken material than the written. An issue of principle is clearly involved, too - namely the nature of the Creole-English continuum typical of the Caribbean. The written language of Jamaica is English; its spoken language is not simply English but a span of the continuum comprising English and the upper mesolectal range – even for the type of educated speaker envisaged as informant in the ICE guidelines.

Associated Research Projects

- Deuber, Dagmar. Style and standards in English in the Caribbean: Morphological and syntactic variation in Jamaica and Trinidad. [Habilitation]

- Rosenfelder, Ingrid. Sociophonetic variation in educated Jamaican English: An analysis of the spoken component of ICE-Jamaica. [Dissertation]

- Jantos, Susanne. Morphosyntax in Educated Jamaican English: a comparison of spoken and written usage in ICE-Jamaica. [Dissertation]

- Höhn, Nicole. Discourse markers in spoken Jamaican English: a corpus-based study. [Dissertation]

The University of the West Indies

The Jamaican Language Unit (JLU)

Background Reading: "The English Language in Jamaica"

Christian Mair & Andrea Sand

The Caribbean – understood here as the West Indian islands (or Antilles) and those portions of the Central and South American mainland which have shared a similar history as slavery-based colonial plantation economies – is one of the culturally and linguistically most heterogeneous and fragmented areas in the world. The Anglophone Caribbean, although just one part of this broader cultural area, itself presents linguistic situations of baffling complexity. The feature common to all states and territories – regardless of whether they are part of the islands (Jamaica, Trinidad & Tobago, Barbados, and many smaller ones) or the mainland (Guyana, Belize) – is that English co-exists with various English-lexicon creole languages, which are extremely vital and widely used by all strata of society in spoken and informal communication. Apart from occasional experimental or literary uses, however, they do not normally appear in writing, and standardised orthographies are confined to specialist circles such as linguists. Depending on the specific context, local English usage has been influenced to varying degrees by contact with other European languages, non-European immigrant languages such as Hindi, Bhojpuri (=Bihari) or Chinese, Creoles with a language other than English as a lexifier, and also by native American languages, many of which are now extinct.

The current situation in most communities can be described as one in which local norms of educated English usage are developing in a forcefield marked by partly conflicting tensions. British English, with an R.P. accent, has been the inherited colonial norm and continues to exercise a strong influence in official language use, in the educational system, and the more conservative segments of the media. Owing to massive emigration and the ever-present influence of U.S. business and media in the region, the influence of North American English is almost equally powerful now. Last but not least, political decolonisation and the attendant development of a new sense of cultural awareness and ethnic pride have led to a profound change in the structure, function and prestige of many of the creole languages of the region. While the structural base of the traditional rural creole "basilect" is gradually being eroded through intensive language contact with English, the resulting modified or "mesolectal" forms of the Creole have lost much of the social stigma traditionally associated with them. British English, the traditional "acrolect", by contrast, has lost some of its prestige and represents a norm more often proclaimed than actually followed.

The chief problem for a linguistic description of Caribbean English usage today is to model the relationship between English and the various English-lexifier creoles of the region. In view of the far-reaching differences in syntax and sound pattern, it would be quite plausible, for example, to consider English and "patois" (the folk designation for Jamaican Creole) two distinct languages. However, this is not the view of most Jamaicans, who tend to think of themselves as English-speaking and therefore regard patois as some kind of English. Nor are utterances mixing English and patois elements good instances of the type of code-switching observed in some truly bilingual communities such as Hispanic speakers in the United States. The majority of linguists who have studied English usage in the region therefore conceive of the complicated polyphony of more English-like and more Creole-like ways of speaking as a "continuum" which provides for gradual but far from random transitions between the two extreme linguistic poles.

Commentators agree that a shared history and cultural heritage, and strong intra-regional mobility have created a variety which can be legitimately referred to as Caribbean English. However, even in educated usage as one inspects more informal and spoken usage local peculiarities persist to a considerable extent, especially in pronunciation and the lexicon. This is why in compiling the "Caribbean" component of ICE it has been decided to sample only texts from Jamaica, the most populous and a culturally very influential community. Many results obtained from analyses of the Jamaican corpus will no doubt reflect usage in the Caribbean as a whole (an assumption which might easily be tested on the basis of further corpora from other parts of the Caribbean at some later stage). A "compound" Caribbean corpus with texts from several Caribbean countries, on the other hand, might have levelled differences in local usage, thus taking for granted a homogeneity of Caribbean language norms which ought to be proved in the description. Also, detailed comparative studies of individual sub-components (e.g. Jamaica vs. Trinidad & Tobago), while useful in some cases, were generally expected to yield inconclusive results on account of the small size of the samples.

As can be seen from the make-up of the current release of ICE-Jamaica (cf. Appendix), which is heavily biassed towards the written component, sampling has been more difficult for the spoken material than the written. In the first place, this is, of course, due to the usual practical problems of obtaining, recording, storing and transcribing spoken language, but an issue of principle is clearly involved, too - namely the nature of the Creole-English continuum briefly described above. The written language of Jamaica is English; patois is present in the form of loans, quotes, and more generally as a substrate indirectly accounting for some peculiarities of local usage. The spoken language of Jamaica, however, is English only in very formal contexts. In informal communication, it is not simply English but a span of the continuum comprising English and the upper mesolectal range - even for the type of educated speaker envisaged as informant in the ICE guidelines. (This is, obviously, one major sociolinguistic difference between Jamaica and other native-speaker communities such as Australia, Britain, or the United States, where educated speakers would not be expected to deviate much from standard English in their lexicon and grammar). Conversations such as S1A-002, in which a stranger to the community (i.e. the ICE team's German research assistant) talks with Jamaicans in an informal atmosphere, are therefore typical with regard to the structural features of Jamaican English they document, but somewhat marginal from a sociolinguistic and functional perspective (communication with foreigners being, after all, a less central task than communication among community insiders).

As regards its place in the ICE bunch of corpora, we hope that the written material assembled in ICE-Jamaica will be analysed by the usual corpus-linguistic and statistical methods, and that such investigations will reveal the structural profile of educated Jamaican English and its relations to other standards. Among the most interesting questions will be whether Jamaican English, the only variety in ICE with a Creole substrate, closely resembles natively spoken standards or whether it also shares some features with the second-language standards emerging in those former colonies in which English is an adopted official language. Given the complexities described and the relatively small amount of text assembled, we suggest that the spoken material should be investigated by qualitative methods such as the ones developed in conversation analysis and the ethnography of speaking.

Publications dealing with ICE-Jamaica:

- Mair, Christian. "Problems in the Compilation of a Corpus of Standard Caribbean English: A Pilot Study." Gerhard Leitner, ed. New Directions in English Language Corpora. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1992. 75-96.

- Mair, Christian, and Andrea Sand. "Caribbean English: Structure and Status of an Emerging Variety." Raimund Borgmeier, Herbert Grabes and Andreas Jucker, eds. Anglistentag 1997: Giessen – Proceedings. Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 1998. 187-98.

- Sand, Andrea. Linguistic Variation in Jamaica: A Corpus-Based Study of Radio and Newspaper Usage. Tübingen: Narr, 1999.

Further reading on English in Jamaica:

- Allsopp, Richard. Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage. Oxford: OUP, 1996.

- Cassidy, Frederic G. Jamaica Talk: 300 Years of the English Language in Jamaica. London: Macmillan, 1961.

- Christie, Pauline. "Questions of Standards and Intra-Regional Differences in Caribbean Examinations." Ofelia Garcia and Ricardo Ortheguy, eds. English across Cultures – Cultures across English: A Reader in Cross-Cultural Comminication. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1989. 243-62.

- Holm, John A. "English in the Caribbean." Robert Burchfield, ed. The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. V.: English in Britain and Overseas. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 328-81.

- LePage, Robert B. "Some Premises Concerning the Standardisation of Languages, with Special Reference to Caribbean Creole English." International Journal of the Sociology of Language 71 (1988): 25-36.

- Patrick, Peter L. Urban Jamaican Creole: Variation in the Mesolect. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1999.

- Roberts, Peter. West Indians and their Language. Cambridge: CUP, 1988.

- Shields, Kathryn. "Standard English in Jamaica: A Case of Competing Models." English World-Wide 10 (1989): 41-53.

Sample Transcription of a Corpus Text (with corresponding audio files)

| Text S1A-002 (excerpt) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text category | spoken – dialogue – private – direct conversations | |||||||

| Recording date | December 08, 1999, 8 pm | |||||||

| Location | SCR, Bar, University of the West Indies, Mona, Kingston 7, Jamaica | |||||||

| Speaker Information | ||||||||

| $A | $B | $C | $D | |||||

| Name | Donald Miller | Enith Noble | John F. Lindo | Dagmar Deuber | ||||

| Gender | male | female | male | female | ||||

| Educational level | university degree | university degree | Ph.D. | M.A. | ||||

| Occupation | manager | librarian | senior lecturer | (interviewer) | ||||

| Nationality | Jamaican | Jamaican | Jamaican | German | ||||

| Age | 46-65 | 46-65 | 26-45 | 26-45 | ||||

| Clip No. | Transcription | Recording |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | <$A><#> I can't speak any way different to the way I speak now <,> | [.mp3] |

| 2. | <#> I tried out for a play once right <#> And I was supposed to play this roughneck Jamaican boy <,> right | [.mp3] |

| 3. | <#> And I read the lines with all the passion and what not and the director said <quote> Thank you </quote> <{> <[> <,> yeah </[> | [.mp3] |

| 4. | <#> So I went to him afterwards and I said uhm <quote> What wrong </quote> <#> And he says <quote> Boy you couldn't convince me and you can't convince nobody </quote> <,> right | [.mp3] |

| 5. | <$C><#> <[> Fuck off </[> </{> <$B><#> <O> laughter </O> You're just not rough <O> laughter </O> |

[.mp3] |

| 6. | <$A><#> <}> <-> If you </-> <=> if you </=> </}> want to try out for the role of the father <,> right <{> <[> <,,> </[> <#> And I thought the father is <}> <-> a </-> <=> a </=> </}> role an image that I could not see myself as <#> I was seventeen years old <#> I can't see myself as this forty-five year old man <}> <-> who's </-> <=> has </=> </}> his children and is dealing with the problems of his children <,> yeah <$C><#> <[> You may </[> <O> laughter </O> |

[.mp3] |

| 7. | <$A><#> I identified with the role of the youth | [.mp3] |

| 8. | <$C><#> What do you identify my <,> the way I speak <#> How do you identify the way I speak | [.mp3] |

| 9. | <$A><#> <}> <-> You you you are </-> <=> you are </=> </}> rural <,> rural typical Jamaican <{> <[> <,> </[> educated <$C><#> <[> me </[> </indig> raas </indig> |

[.mp3] |

| 10. | <$C><#> Educated me <,> I'm rural typical <$A><#> Sorry sorry <}> <-> <.> urb /.> </-> <=> yeah rural </=> </}> <,> rural typical <{> <[> <,> </[> yeah <$C><#> <[> Yeah </[> </{> I sound like a country boy <,> with an education <$A><#> You sound like a <,> but like our prime minister same country boy with an education <#> <unclear> one-word </unclear> come on give me a break here |

[.mp3] |

| 11. | <$B><#> No no no but John <,> you sound like <,> most of the intellectuals around quite frankly <O> laughter </O> <,> okay <,> <}> <-> or </-> <=> or </=> </}> the leading group of intellectuals around <$A><#> But Enith <[> Enith Enith </[> <$B><#> <[> You know </[> </{> <,> you and I sound alike <#> You and I are from country and we are <{> <[> educated </[> <$A><#> <[> Thank you very much Enith </[> |

[.mp3] |

| 12. | that's the point I was about to make <,> that ninety per cent of us <{1> <[1> in Kingston <,> right <,> </[1> have country origins <,,> which is where we got our first education <{2> <[2> <,,> right </[2> first introduction to the language <#> And we had some very rigid and strict <{3> <[3> teachers </[3> who rapped you on your knuckles or whatever right and made you pronounce words properly and all of this <indig> raatid </indig> <$B><#> <[1> Yeah yeah yeah yeah </[1> </{1> <$C><#> <[2> And our first introduction to the language </[2> </{2> <$B><#> <[3> Exactly exactly </[3> </{3> <$C><#> And you think I sound like country boy with an education <$A><#> No you sound I did not say <{> <[> you sound like a country boy </[> <$B><#> <[> No the country boy thing <}> <-> is is </-> <=> is </=> </}> not a nice connotation </[> <O> laughter </O> |

[.mp3] |

| 13. | <$C><#> You think I sound like <}> <-> a <,> </-> <=> a </=> </}> man with rural origins | [.mp3] |

| 14. | <$B><#> What I have always maintained John is that uh <,> all the people from the countryside they come into Kingston <,> and the people from Kingston go to Miami <,> okay <{1> <[1> <,> </[1> so we rule Kingston <{2> <[2> <,> </[2> okay <$A><#> <[1> Exactly </[1> </{1> <$A><#> <[2> Exactly </[2> </{2> |

[.mp3] |

| 15. | <$C><#> Yes <,> but when I came to Kingston I was very shocked <,,> <#> I'll tell you when I went to school I was very shocked <unclear>one-or-two-words</unclear> dropping the aitches <unclear> two-or-three-words </unclear> <#> When I came to Kingston I realised people didn't know the difference between <mention>pardon me</mention> and <,> <#> What was I thinking <,> <#> They didn't know the difference between <mention>sorry</mention> and <mention>excuse me</mention> <$A><#> All I saying <O> laughter </O> <$C><#> A man who wants to walk past you and he says <quote> Excuse me please </quote> he says <quote> Sorry </quote> <{1> <[1> <,> </[1> yeah and <unclear>one-or-two-words</unclear> <{2> <[2> <,> and </[2> |

[.mp3] |

| 16. | the other thing I learned <}> <-> I I I </-> <=> I </=> </}> came to Kingston <}> <-> to </-> <=> to </=> </}> attend sixth form <,,> and <$A><#> <[1> Yeah sorry for what <#> What you sorry for </[1> </{1> <$B><#> <[2> That's a recent thing </[2> </{2> <$A><#> So I was right you're a damn country boy <}> <-> who who </-> <=> who </=> </}> <{> <[> <}> <-> get a </-> </[> <=> get a </=> </}> good education <$C><#> <[> I'm a country boy </[> <$B><#> Oh darling I'm trying to get away from this country boy <{> <[> thing </[> <$C><#> <[> I'm a country boy </[> <$B><#> That's insane <O> laughter </O> <$A><#> <}> <-> I was </-> <=> I was </=> </}> born in Ewarton <#> I'm a country boy myself <$B><#> Were you darling <#> I thought you were born and bred <$C><#> Under the clock <,> <#> No darling no such luck <#> I born in Ewarton St Catherine country <,> <#> And when I born <,> it was country because they didn't even have electricity <,> |

[.mp3] |

| 17. | <$B><#> Dagmar I'm so glad you came because all this that comes out I never knew this about this chap <O> laughter </O> | [.mp3] |

| 18. | <$C><#> But the first time in my life that I came to Kingston <,> I went <}> <-> to </-> <=> into </=> </}> the canteen and I said <quote> Could I have <,> uhm <,> a box of milk please </quote> <#> And the man said to me <,> <quote> Do you want white milk </quote> <,> <O> laughter </O> <#> And I said <{1> <[1> <,,> </[1> I said <quote> Is there another kind </quote> he said <quote> Yes <{2> <[2> there is chocolate milk and cherry milk </quote> </[2> <$B><#> <[1> Is there another <O> laughter </O> </[1> </{1> <$A><#> <[2> Chocolate milk and cherry milk yeah <O> laughter </O> </[2> </{2> <#> You never know that <O> laughter </O> |

[.mp3] |

| 19. | <#> We used to have a joke about country people coming to Kingston and seeing <,> street lights <,> <#> Yeah a little country child coming to Kingston and says <quote> Mama mama <,> <indig> moon pon tik </indig> </quote> <,> right a moon on a stick yeah <,,> <#> Well that was John yeah | [.mp3] |

| 20. | <$C><#> I must say that when I came to Kingston I was most shocked <,> to realise that <}> <-> people did <.> peo </.> </-> <=> people </=> </}> would not go into a shop and say <quote> Could I have some milk please </quote> <{> <[> they'd say </[> <quote> Could I have some white milk </quote> <,> as opposed to some chocolate milk <,> cherry milk <$A><#> <[> <?> Please </?> </[> </{> <$B><#> We have always known that Kingston people stupid <{> <[> <,> </[> right <O> laughter </O> <$A><#> <[> Yes </[> </{> <$A><#> And rude and <{1> <[1 rude and </[1> rude and rude and rude and rude yeah <,,> <$B><#> <[1> Yes </[1> </{1> |

[.mp3] |

| 21. | <$A><#> But <}> <-> is is </-> <=> is </=> </}> all a cultural thing uhm <,,> <#> Language in Jamaica is <,,> strange because <,,> it's diversified in that each community across Jamaica speaks its own special <,> patois <#> There are words that are used in St Thomas that are not used in St Elizabeth <{2> <[2> <,> <}> <-> in terms of </-> <[/2> <=> in terms of </=> </}> <}> <-> the the the the the </-> <=> connoting </=> </}> a message in a language right | [.mp3] |

<$X>- Speaker ID

- <#>

- Text unit markers (~ individual sentences)

- <,>

- Short pause (approximately one syllable)

- <,,>

- Longer pause (two syllables and more)

- <$A> ... <{> <[> ... </[> ...

<$B> ... <[> ... </[> </{> ... - Overlaps (two or more speakers talking simultaneously)

- <quote> ... </quote>

- Quotations

- <mention> ... </mention>

- Words or phrases discussed in the text

- <indig> ... </indig>

- Words, expressions or phrases from Jamaican Creole

- <O> laughter </O>

- Laughter and other paralinuistic utterances

- <}> <-> ... </-> <=> ... </=> </}>

- Repetitions, hesitations, self-corrections

- <.> ... </.>

- Incomplete word

- <?> ... </?>

- Uncertain transcription

- <unclear> ... </unclear>

- Incomprehensible word(s)

ICE-Jamaica – Text Categories & Codes

SPOKEN (300) | ||

|---|---|---|

DIALOGUE (180) |

S1 | |

Private |

(100) |

S1A |

| direct conversations | (90) | S1A-001 to S1A-090 |

| distanced conversations | (10) | S1A-091 to S1A-100 |

Public |

(80) |

S1B |

| class lessons | (20) | S1B-001 to S1B-020 |

| broadcast discussions | (20) | S1B-021 to S1B-040 |

| broadcast interviews | (10) | S1B-041 to S1B-050 |

| parliamentary debates | (10) | S1B-051 to S1B-060 |

| legal cross-examinations | (10) | S1B-061 to S1B-070 |

| business transactions | (10) | S1B-071 to S1B-080 |

MONOLOGUE (120) |

S2 | |

Unscripted |

(70) |

S2A |

| spontaneous commentaries | (20) | S2A-001 to S2A-020 |

| unscripted speeches | (30) | S2A-021 to S2A-050 |

| demonstrations | (10) | S2A-051 to S2A-060 |

| legal presentations | (10) | S2A-061 to S2A-070 |

Scripted |

(50) |

S2B |

| broadcast news | (20) | S2B-001 to S2B-020 |

| broadcast talks | (20) | S2B-021 to S2B-040 |

| speeches (not broadcast) | (10) | S2B-041 to S2B-050 |

WRITTEN (200) | ||

NON-PRINTED (50) |

W1 | |

Non-professional writing |

(20) |

W1A |

| student untimed essays | (10) | W1A-001 to W1A-010 |

| student examination essays | (10) | W1A-011 to W1A-020 |

Correspondences |

(30) |

W1B |

| social letters | (15) | W1B-001 to W1B-015 |

| business letters | (15) | W1B-016 to W1B-030 |

PRINTED (150) |

W2 | |

Informational (learned) |

(40) |

W2A |

| humanities | (10) | W2A-001 to W2A-010 |

| social sciences | (10) | W2A-011 to W2A-020 |

| natural sciences | (10) | W2A-021 to W2A-030 |

| technology | (10) | W2A-031 to W2A-040 |

Informational (popular) |

(40) |

W2B |

| humanities | (10) | W2B-001 to W2B-010 |

| social sciences | (10) | W2B-011 to W2B-020 |

| natural sciences | (10) | W2B-021 to W2B-030 |

| technology | (10) | W2B-031 to W2B-040 |

Informational (reportage) |

(20) |

W2C |

| press news reports | (20) | W2C-001 to W2C-020 |

Instructional |

(20) |

W2D |

| administrative/regulatory | (10) | W2D-001 to W2D-010 |

| skills/hobbies | (10) | W2D-011 to W2D-020 |

Persuasive |

(10) |

W2E |

| press editorials | (10) | W2E-001 to W2E-010 |

Creative |

(10) |

W2F |

| novels/short stories | (20) | W2F-001 to W2F-02 |

International Corpus of English – Jamaica Component

Compiled at the University of Freiburg | English Department, 79085 Freiburg, Germany

and at the University of the West Indies, Mona, Kingston 7, Jamaica

Contact: Hubert Devonish & Christian Mair

F-LOB and Frown

Part-of-speech tagging for the Freiburg updates of the LOB and Brown corpora

The Freiburg updates of the well-known LOB and Brown reference corpora of British and American English (F-LOB and "Frown" for short) have been used with profit in a large number of studies on ongoing linguistic change in present-day English, both by our Freiburg-based research team and others.

"Tagged" versions of the corpora, that is versions in which each word is followed by an automatically assigned and manually post-edited part-of-speech indicator, a "tag", (cf. example text) has greatly expanded the range of investigations which can be carried out on the basis of this valuable material. For example, rather than look for individual instances of phrasal verbs, it is possible to ask whether verb+particle combinations as a group have become more frequent, or whether there have been shifts in the relative frequency of nouns or verbs in individual genres or in the language as a whole. This project was undertaken jointly with Prof. Geoffrey Leech's team at Lancaster.

The F-LOB and Frown corpora consist of the same text categories as LOB and Brown (cf. table) – each corpus consists of 500 texts of about 2,000 words each, all of them written, edited, and published, which amounts to a total of about one million words per corpus.

ARCHER – A Representative Corpus of Historical English Registers

In its original form this corpus was compiled under the direction of Prof. Douglas Biber at the University of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, its aim being a balanced documentation of various textual genres in British and American English since ca. 1650. The material – amounting to a total of about 1.7 million words – has been used by many scholars for a wide variety of investigations on recent linguistic change and change in discourse and genre conventions. Prof. Mair has undertaken to collaborate with the original compilers and a number of other leading academic institutions in the field of historical English on a revised and expanded version of this corpus.

Work on ARCHER is currently being coordinated at the University of Manchester (UK).

www.projects.alc.manchester.ac.uk/archer

"World Languages – Digital Languages"

Studying varieties of English around the world

within the framework of the sociolinguistics of globalisation

This ongoing research project, which is being undertaken in close collaboration with Prof. Dr. Stefan Pfänder and his group from the Romance Department, aims to develop the study of "varieties of English around the world" (aka the "New Englishes" or "World Englishes") by integrating it into the emerging research paradigm of the sociolinguistics of globalisation.

In addition to the more traditional fully fledged and territorially based varieties dominantly used in face-to-face interaction, the study of World Englishes increasingly has to reckon with global linguistic flows of deterritorialized vernacular resources, which come to the fore, for example, in digitally mediated communication, where they are available for the fashioning of subcultural styles or ethnolinguistic repertoires. This part of the research has been funded by the German Research Foundation from 2011 to 2015 – DFG project "'Cyber-Creole:' Jamaican Creole als Kontaktvarietät unter den Bedingungen globalisierter und computergestützter Kommunikation".

The more dominant English is globally, the more heterogeneous it becomes internally. The farther the language spreads, the more it is affected by the multilingual settings in which it is being used. "Natural" links between vernaculars and their territories or primary communities of speakers are becoming weaker, as migrations and media encourage the flow of linguistic resources. On such a view, the English language, the undisputed world language of the present era, is not an amalgam of separate varieties, each with its own history and each captured by listing its phonological, morphosyntactic, and lexical properties. Rather, English is a pool of standard and nonstandard resources of varying and fuzzy regional and temporal reach.

A world which is marked by criss-crossing global currents of migration of historically unparalleled intensity and an increasingly all-encompassing global "mediasphere" (Arjun Appadurai) provides a linguistic ecology in which, at least in principle, all Englishes are everywhere. However, this does not mean that the world will therefore become a more homogeneous, Anglophone communicative space. To appreciate this, it is sufficient to look at major metropolitan centres in the English-speaking world, such as London, New York, Sydney or Toronto, which have long been or have recently developed into hot spots of urban multilingualism.

CLARIN-D – Common Language Resources and Technology Infrastructure - Deutschland

[May 2011 – April 2014]

CLARIN-D is a web- and centres-based research infrastructure for the social sciences and humanities. Funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) for an initial period of three years, it provides the following linguistic data, tools and services, among others:

CLARIN-D is a web- and centres-based research infrastructure for the social sciences and humanities. Funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) for an initial period of three years, it provides the following linguistic data, tools and services, among others:

- archives, corpora and dictionaries of various languages;

- tools for the annotation of written and spoken language data, as well as videos;

- WebLicht, a service-oriented architecture for creating annotated text corpora.

Since May 2011, Prof. Mair has been the head of the CLARIN consortium's discipline-specific working group on foreign-language philologies. The working group consists of leading figures in linguistics, cultural and literary studies in the fields of English, Romance and Slavic Studies at various German universities. Working in close collaboration with the CLARIN-D service centres, the group is to give advice on research priorities, so that infrastructure development can best meet the needs of the larger research community. One of the major functions of the working group is to propose and develop so-called curation projects – data, tools or services, which are of particular interest to the research community – which will then be integrated into the CLARIN-D infrastructure and made available on the web.