Professor Lemke | Informationen & Handouts

Length of Written Assignments

Double spaced, word count +/- 10%

- Bachelor's Thesis

14.000–15.000 words (c. 35-40 pages) - Zulassungsarbeit

24.000 words (c. 60 pages) - Master's Thesis

32.000 words (c. 80 pages) - Term Paper

Proseminar: 6.000 words (c. 15 pages)

Hauptseminar: 7.500–8.500 words (c. 18-20 pages)

Masterseminar: 9.000–1000 words (c. 20-25 pages)

Handouts

Style Sheet

HOW TO STRUCTURE YOUR PAPER

TITLE PAGE

The title page is not numbered. Please provide the following information:

- Semester

- Type and title of the course

- Lecturer's name

- Title of your paper

- Your name & address

- Your e-mail

- Fachsemesterzahl

TABLE OF CONTENTS

For papers of 10 or more pages, please provide a table of contents. It will help you in structuring your ideas. Furthermore, you should practice writing an academic paper because these skills are required for your Bachelor's- or Master's Thesis (at the very latest).

Make sure your system of numbering your chapters or sections is consistent and 'reasonable', i.e. do not subdivide a 10-page-paper into 10 chapters! Usually, the page containing the table of contents is not numbered. Chapter headings should give an indication of your argument (i.e. do not use "Chapter 1" or "Main Part").

INTRODUCTION

You introduce your readers to the general topic, and then introduce the specific thesis you will discuss. This thesis must be clearly stated in the introduction. You should also tell your readers how you will go about your task, indicating the structure of your argument.

MAIN PART

In this part, you are expected to prove the thesis you put forward in the introduction. Make sure that your arguments are logical in themselves and follow a logical order. You should go through your arguments step by step and you should give sufficient reasons for the claims you make. A division into chapters and, where suitable, subchapters will help you to structure your argument.

Give sufficient examples from the text you are analyzing to illustrate your argument. Integrate relevant opinions from secondary sources; always acknowledge these sources, even when you do not directly quote them but paraphrase them. When you are quoting material, make sure you tell your readers what you are trying to show with this quote.

CONCLUSION

Briefly summarize your initial thesis and the conclusion you have reached. Do not present new material, thoughts, etc.

BIBLIOGRAPHY / WORKS CITED

Make sure you include all the articles, books, websites, etc. you have quoted from or referred to in your text. Do not include material you have not referred to.

For the style of the bibliography / works cited, see below.

QUOTATIONS & DOCUMENTATION

Demonstrate in your paper that you know how to look for and use secondary sources (like books, or scholarly articles in books or journals, or reliable pages from the internet). In a proseminar you are expected to use at least three different secondary texts, in a masterseminar you should use at least 5 to 10 books or articles.

What secondary literature do you need? Of course, you should check if somebody has already been written on your topic – but make sure that you do not simply follow the argumentative structure of an article. However, you might also need secondary sources to define terms you use, or to provide 'background' information about the novel, the time of its writing, initial responses to the text, etc.

Make sure you integrate quotes into your argument. Quotes cannot replace an argument. You can use quotes to back up your argument, but also to point out where you disagree with other critics. When quoting primary or secondary sources, make sure to be precise. Use square brackets [ ] to mark all additions and changes to the grammatical structure (e.g. changing "my" to [his] when incorporating a quote into your sentence structure). Use [...] to mark omissions. If there is a mistake in the original, you mark it with [sic].

Example: According to John Doe, David Copperfield is a "novel of deveopment [sic]" (25).

►►► You have to document all cases where you quote or use somebody else's text!

Plagiarism is the most severe 'crime' in the humanities. If found out, you will not receive credit and you will not be given the opportunity to write an alternative paper for the course. And please remember: If you are able to find it on the internet, we will also be able to find it ... See also Good Academic Practice

DOCUMENTING YOUR SOURCE(S)

If you are quoting short passages (up to three lines of text), you integrate them into your own text. Use English quotation marks ("English quotation marks" vs. „deutsche Anführungszeichen"). Bibliographical information is then added at the end of your sentence in parentheses (author page). If you already name the author in the sentence, only the page reference is cited in brackets. The same applies if you are paraphrasing/not quoting directly from a secondary source.

Example:

- In this poem, Wordsworth "transgresses the boundaries of human nature to reach the heights of pure spirit" (Johnson 34).

- Johnson argues that in this poem Wordsworth "transgresses the boundaries of human nature to reach the heights of pure spirit" (34).

- Johnson argues that Wordsworth's poem transcends the realm of the human (34).

If you quote longer passages (usually more than 3 lines of quoted text/40 words), you should set this quotation off as a separate paragraph, indented on the left by some 1.25 cm (you can also use a double indent on the left and the right). If text passages are italicized, indicate whether the emphasis is in the original text or your addition.

Example:

The autonomy of the fictional universe leads Dorrit Cohn to the conclusion that historiography may be emplotted, but not novels:

A novel can be said to be plotted but not emplotted: its serial moments do not refer to, and cannot therefore be selected from, an ontologically independent and temporally prior data base of disordered, meaningless happenings that it restructures into order and meaning. In this respect the process that transforms archival sources into narrative history is qualitatively different from [...] the process that transforms a novelist's sources [...] into his fictional crea- tion (781, original emphasis).

Note that no quotation marks are used with indented passages. The bibliographical information is added after the quotation. There is no full stop after the brackets.

WORKS CITED

Please see pdf above.

Thesis Statement

DEFINITION

A thesis statement is a short statement, usually one sentence, that summarizes the main point or claim of an essay, research paper, etc., and is developed, supported, and explained in the text by means of examples and evidence.

Source

The thesis statement is a one or two sentence encapsulation of your paper's main point, main idea, or main message. Your paper's thesis statement will be addressed and defended in the body paragraphs and the conclusion.

Source

[A thesis statement] is a single sentence that formulates both your topic and your point of view. In a sense, the thesis statement is your answer to the central question or problem you have raised. Writing this statement will enable you to see where you are heading and to remain on a productive path as you plan and write. Try out different possibilities until you find a statement that seems right for your purpose. Moreover, since the experience of writing may well alter your original plans, do not hesitate to revise the thesis statement as you write the page.

MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, 42

EXAMPLES

- a) In this paper, I will discuss whether fast food is bad for children's health.

versus

b) In a case study of three TV commercials, this paper assesses how the market industry conceals how fast food causes serious harm to children's health. - a) Hollywood movies depict stereotypical gender roles.

versus

b) In a comparison of the movies Juno and Precious, this paper reveals how contemporary "Coming-of-Age- Movies" subvert stereotypical gender roles - a) Laurie Penny's Meat Market. Female Flesh Under Capitalism is a feminist book.

ᐅ This statement, although it does state something, does not provide the reader with specific reasons why Penny's book can be read as feminist or what feminist statements the author makes.

versus

b) Laurie Penny's Meat Market. Female Flesh Under Capitalism can be read as a feminist book, disclosing women's struggles in a neo-liberal age.

ᐅ This statement hints at the theoretical context that the paper will assess and it gives an idea on the specific perspective that the author pursues: With a feminist reading of the text, he/she will focus on the problematic of neo-liberalism and the specific burdens it creates for women. - a) Shakespeare's Hamlet is a play about a young man who seeks revenge.

ᐅ That does not say anything – it is basically just a summary and hardly debatable.

versus

b) Hamlet experiences conflicting feelings because he is in love with his mother.

THINGS YOU SHOULD DO WHEN COMPOSING A THESIS STATEMENT

- Your thesis should indicate your original point, idea, or argument

- A thesis statement should be one or two quality sentences

- Write a thesis that is specific, not general

- Clarity for the reader should be important when writing a thesis statement. Your thesis should include your position on the topic

- Your thesis statement must be debatable

- Finally, you should realize that your initial thesis statement is subject to change! The more research you do and the more you revise your paper, the more you will mold a thesis statement that will succinctly describe what your final draft proposes to argue.

Prose

Definition

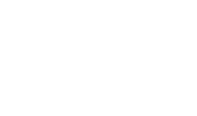

The theory of narrative, or narratology, focuses on the complex structures that constitute Ftehhelnerar!ration of a story. It attempts to give a precise and systematic account of textual structures.

Narrator

- the imagined 'voice' transmitting the story

- Narrators vary according to their degree of participation in the story:

- first-person narratives: involved either as witnesses or as participants in the events of the story

- third-person narratives: stand outside those events

- omniscient narrator: outside the events but has special privileges such as access to characters' unspoken thoughts, and knowledge of events happening simultaneously in different places

- Narrators also differ in the degree of their overtness:

- some are given noticeable characteristics and personalities (as in first-person narratives and in some third-person narratives)

- 'covert' narrators are identified by no more than a 'voice' (as in most third-person narratives)

- Further distinctions are made between reliable narrators, whose accounts of events we are obliged to trust, and unreliable narrators, whose accounts may be partial, ill- informed, or otherwise misleading

Focalization

- Adoption of a limited 'point of view' from which the events of a given story are witnessed, usually by a character within the fictional world

- Unlike the 'omniscient' perspective of traditional stories, which in principle allows the narrator privileged insight into all characters', a focalized narrative constrains its perspective within the limited awareness available to a particular witness, to whom the thoughts of other characters remain opaque

- "Showing" vs. "telling": a focalizing observer is not necessarily the narrator of the story, but may be a character in an account given by a third‐person narrator

Different ways to represent inner feelings and thoughts

- Psycho-narration

- Free indirect discourse

- Interior monologue

A few critical terms

Ambiguity allows for two or more simultaneous interpretations. Deliberate ambiguity can contribute to the effectiveness and richness of a work. It is often possible to resolve the ambiguity of a word, phrase, situation, or text by analyzing the context of a work.

Irony indicates a contradiction between an action or expression and what is meant, between the literal and the intended meaning of a statement; one thing is said and its opposite implied (e.g. "Beautiful weather, isn't it?" when it's raining). Ironic literature stresses the paradoxical nature of reality and the contrast between an ideal and actual condition. (If used harshly, contemptuously for destructive purposes, it is sarcasm.)

Satire usually implies the use of irony or sarcasm. As a literary genre, it is very polemical and often directed at public figures, conventional behavior, social or political conditions, or it attacks human folly or vice.

Film

Image + Sound + Narrative + Performance → FILM

I. THE IMAGE

The visual code. The smallest unit is a frame showing a single picture. If one projects a sequence of twenty-four frames per second on a screen, the human eye is deceived into seeing a moving image. A shot (Einstellung) is a sequence of frames filmed in a continuous (uninterrupted) take of a camera. A take stops when the camera stops rolling or goes offline. A sequence of shots makes up a scene. A scene is a sequence of action segments which take place, continuously, at the same time and in the same place. When you jump from place to place, or from time to time, it is a new scene.

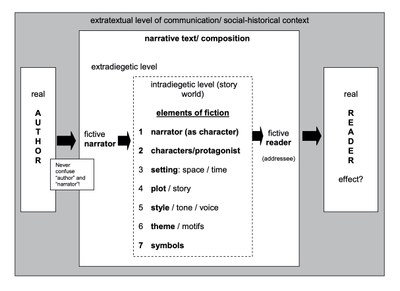

Shot types are based on two distinguishing features:

- the camera's distance from the object

- the size of the object; the four central categories are close-up, medium shot, full shot, and long shot

- Extreme close-up. A small object or part of an object shown large (a speaking mouth, a telephone receiver). Often a detail shot shows a plot-relevant object – a ring, a telephone number on an envelope, etc.

- Close-up, close shot. Full view of, typically, a human face. (semi-close-up shows the upper third of a person's body)

- Medium shot. A view of the upper half of a person's body.

- American shot. A three-quarter view of a person, showing her or him from the knees up.

- Full shot. A full view of a person (Halbtotale)

- Long shot. (total) A view from a distance, of a large object or a collection of objects (e.g., of buildings, a bridge). Often used to establish a setting (establishing shot). People, when present, are reduced to indistinct small shapes.

- Extreme long shot. A view from a considerable distance (e.g., the skyline of a city). If people can be made out at all, they are mere dots in the landscape.

Frame rate

24 frames per second is the normal projection speed. Increasing the speed of the frame rate during filming is called slow motion, decreasing it is called fast motion. Freeze frame occurs when a single frame is repeated.

Camera Movement

Usually, the camera is assumed to be shooting from a stationary position. If the camera changes its position while filming we get the following types of 'dynamic shots':

- pan. The camera surveys a scene by tilting around its vertical or horizontal axis.

- tracking shot/pulling shot. The camera follows (tracks) or precedes (pulls) an object which is in motion itself.

- push in, pull back. The camera moves towards or away from a stationary object.

- zoom (the camera actually remains stationary). The camera's lens moves towards or away from an object (zooming in, zooming out) by smoothly extending or shortening its focal length. Normally, this is recognizable as apparent motion only because the object retains its original perspectival aspect (and the camera actually remains stationary). Zoom shots are frequently used to direct attention to a particular detail.

- dolly shot. A shot taken from a camera mounted on a wheeled platform (a dolly). Normally used for moving through a location -- e.g., a dolly shot of a wedding party. "The camera dollies past a queue of guests waiting to be let in".

- crane shot. Camera is mounted on a crane structure.

Camera angles are a result of the camera's tilt: upwards, downwards, or sideways.

- straight-on angle. The camera is positioned at about the same height as the object, shooting straight and level (this is the default angle).

- high angle. The object is seen from above (camera looking down). (An aerial shot is a bird's-eye view taken from a helicopter).

- low angle. The object is seen from a low-level position (camera looking up).

Editing

- Continuity Editing. A system of cutting to maintain continous and clear narrative action.

- Cutting. A cut marks the shift from one shot to another. It is identified by the type of transition which is produced. The two major kinds of cuts are 'direct' and 'transitional'. The direct cuts are as follows:

- direct cut, straight cut. An immediate shift to the next shot without any transition whatsoever.

- jump cut. Leaving a gap in an otherwise continuous shot. The gap will make the picture "jump". Jump cuts are indicative of either careless editing, or they may be used for intentional effect. They disrupt normal models of continuity editing.

- shot/ reverse shot. Two or more shots edited together that alternate characters, typically in a conversation situation. Characters in one framing usually look left, in the other framing, right.

Transitional cuts, in contrast, are based on an optical effect and usually signal a change of scene:

- fade out (to color) ... fade in. The end of a shot is marked by fading out to an empty screen (usually black); there is a brief pause; then a fade in introduces the next shot.

- dissolve. A gradual transition created by fading out the current shot and at the same time fading in the new shot (creating a brief moment of superimposition).

- swish pan. A brief, fast pan from object A in the current shot to object B in the next.

- wipe. A smoothly continuous left-right (or up-down etc.) replacement of the current shot by the next. Somewhat reminiscent of turning a page.

II. SOUND

- diegetic sound (indigenous sound). Noise, speech or music coming from an identifiable source in the current scene. For instance, we hear a weather report and we see that it comes from a car radio which somebody has just turned on.

- nondiegetic sound. Noise, speech or music which does not come from a source located in the current scene. For instance, we see waves breaking on a desolate sea- shore and we hear Sea Symphony. This supplied sound usually creates mood.

- ambient sound. A diegetic background sound such as the clatter of typewriters in an office or the hubbub of voices in a cafe.

- voice over. (a) Representation of a non-visible narrator's voice; (b) representation of a character's interior monologue (the character may be visible but her/his lips do not move).

III. NARRATIVE

Narration. First, remember that not all films make use of narrators. If and when they are present, filmic narrators come in two kinds depending on whether they are visible on-screen or not.

- flashback. An alteration of story order in which the plot moves back to show events that have taken place earlier.

- flashforward. An alteration of story in which the plot presentation moves forward to future events and then returns to the present.

- off-screen narrator, also voice-over narrator. An unseen narrator's voice uttering narrative statements.

- on-screen narrator. A narrator who is bodily present on screen, acting and talking to the (or an) audience, shown in the act of producing his or her narrative discourse.

Depending on whether narrators tell a story in which they were involved themselves, or a story about others, they are either 'homodiegetic' or 'heterodiegetic':

- homodiegetic narrative. The story is told by a narrator who is present as a character in the story.

- heterodiegetic narrative. The story is told by a narrator who is not present as a character in the story.

Focalization. The ways and means of presenting information from somebody's point of view. Focalization can be determined by answering the question Whose point of view orients the current segment of filmic information? Or: Whose perception serves as the current source of information? Perception includes actual as well as imaginary perception (such as visions, dreams, memories).

The basic concept in focalization theory is focus, and this term refers to two intricately related things:

- the position from which something is seen – the focalizer

- the object seen 'in focus' – this is the focalized object or 'center of attention'.

Consequently, in film analysis, we will often ask two questions: Who sees and what is the object (thing or human being) that the focalizer focuses on?

- point of view shot, POV shot. The camera assumes the position of a character and shows the object of his or her gaze what the character would see.

- gaze shot. A picture of a character looking ('gazing') at something not currently shown. A gaze shot is usually followed by a POV shot.

- eye-line shot. A sequence of two shots: a gaze shot followed by a POV shot. Shot 1 shows the face of a character gazing at something.

- over-the-shoulder shot. The camera gets close to, but not fully into, the viewing position of a character

- reaction shot. A shot showing a character reacting (with wonder, amusement, annoyance, horror, etc.) to what s/he has just seen.

IV. PERFORMANCE

Acting. There is enormous historical and cultural variation in performance styles in the cinema. Early melodramatic styles, clearly indebted to the 19th century theater, gave way to a relatively naturalistic style. There are many alternatives to the dominant style: the kabuki- influenced performances of kyu-geki Japanese period films, the use of non-professional actors in Italian neorealism, the typage of silent Soviet Cinema; there are the improvisatory practices of directors like John Cassavettes or Eric Rohmer, the slapstick comedy of Laurel and Hardy, or the deadpan of Buster Keaton, not to mention the exuberant histrionics of Bollywood films.

Mise-en-scène. All of the elements placed in front of the camera to be photographed/shot: the settings and props, lighting, costumes and makeup, and figure behavior.

Special effects. A general term for various photographic manipulations that that create fictitious spatial relations in the shot, such as superimposition (Übereinanderlagerung), matte shots (different areas of the shot taken separately and combined in laboratory work), and rear projections (foreground filmed against a screen; background imagery is projected from behind the screen).